archive of the Charles Babbage Institue:

http://www.cbi.umn.edu/collections/archmss.html

<< preface

it is also meant to be an additional resource of information and recommended reading for my students of the prehystories of new media class that i teach at the school of the art institute of chicago in fall 2008.

the focus is on the time period from the beginning of the 20th century up to today.

>> search this blog

2008-07-18

>> Charles Babbage Institute

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

8:45 PM

0

replies

tags -

archive,

publications

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> David Moises

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

8:30 PM

0

replies

tags -

artists

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

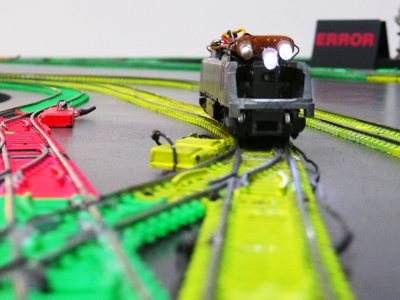

>> David Moises, Severin Hoffmann, "Turing Train Terminal", 2004

from the artists' website: http://www.monochrom.at/turingtrainterminal/abstract_eng.htm

from the artists' website: http://www.monochrom.at/turingtrainterminal/abstract_eng.htm

"Scale trains have existed for almost as long as their archetypes, which were developed for the purposes of traffic,

transportation and trade. Economy and commerce have also been the underlying motivations for the invention of

computers, calculators and artificial brains. Allowing ourselves to fleetingly believe in an earlier historical miscalculation that "... Computers in the future may have

Allowing ourselves to fleetingly believe in an earlier historical miscalculation that "... Computers in the future may have

only 1,000 vacuum tubes and perhaps weigh 1 1/2 tons." (Popular Mechanics, March 1949), we decided to put some

hundred tons of scaled steel together in order to build these calculating protozoa. The operating system of this

reckoning worm is the ultimate universal calculator, the Turingmachine, and is able to calculate whatever is capable of

being calculated. One just would have to continue building to see where this may lead..." "There are three types of points in the layout.

"There are three types of points in the layout.

- The lazy points look the same but appear in different colors;

- And the most common point is the sprung point, which is drawn with a clear preference for the route of the train.

In order to prep the layout for input, all distributors and lazy points have to be set to 0. This is done, by pressing the RESET-Button. Now, the tape is set to 000.

To set the input to the tape, press the red SET-Buttons. So to set up the input 1+1 on the three-block layout, you need to send the train to the outer two SET lines: 1 0 1. Then press SET1, leave SET2 untouched and press SET3. These Buttons control the three points on the yellow ringline. Afterwards the green RUN-Button lets the train first write the INPUT-value into each read/write head. It then gets directed into the SET1 read/writehead and comes back out on that line. This has effectively set the digit stored in that block on the "tape" to 1. It passes the SET2 point, moves into SET 3 and sets this value to 1. Now the Input 1 0 1 is set - visible through the I/0-lamps.

The next station is the START point – Once the locomotive enters the system from that point the calculating starts. Now watch the train as it leaves again and finds a rest at the start point. The altered state, visible on the lamps, is the result. In this example 1 1 0, actually means 2 in the notation of this apparatus.

CALCULATING PROCEDURE

To set up the train set for a calculation it needs to be re-set. By pressing the yellow RESET Button all points get set to the value "0". This is visible through the three 1/0-lightsigns.

Now one can re-set the machine, by pressing the red SET-Buttons. After this the

locomotive is ready to calculate and it gets started with the green RUN-Button.

First the requested value gets written into the read/write-head (pink and orange) and then the train enters the system at the start-rail and gets directed through the system as the points have been pre-set and eventually leaves after a while. The altered state is the result.

The following operations can be calculated:

Input Output

0+0 000 000 = 0

0+1 010 100 = 1

1+0 100 100 = 1

1+1 101 110 = 2

0+2 011 110 = 2

2+0 110 110 = 2

background info: http://www.monochrom.at/turingtrainterminal/Chalcraft.pdf

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

8:25 PM

0

replies

tags -

artists,

interactive art,

media art

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> interview with J. Presper Eckert

from: http://www.cbi.umn.edu/oh/display.phtml?id=120

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

6:16 PM

0

replies

tags -

computer history,

interview,

text

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Stelarc

go and visit his site: http://www.stelarc.va.com.au/arcx.html

go and visit his site: http://www.stelarc.va.com.au/arcx.html

absent body

We mostly operate as Absent Bodies. THAT'S BECAUSE A BODY IS DESIGNED TO INTERFACE WITH ITS ENVIRONMENT - its sensors are open-to-the-world (compared to its inadequate internal surveillance system). The body's mobility and navigation in the world require this outward orientation. Its absence is augmented by the fact that the body functions habitually and automatically. AWARENESS IS OFTEN THAT WHICH OCCURS WHEN THE BODY MALFUNCTIONS.

Reinforced by Cartesian convention, personal convenience and neurolo gical design, people operate merely as minds, immersed in metaphysical fogs. The sociologist P.L. Berger made the distinction between "having a body" and "being a body". AS SUPPOSED FREE AGENTS, THE CAPABILITIES OF BEING A BODY ARE CONSTRAINED BY HAVING A BODY.

Our actions and ideas are essentially determined by our physiology. We are at the limits of philosophy, not only because we are at the limits of language. Philosophy is fundamentally grounded in our physiology . . .

obsolete body

It is time to question whether a bipedal, breathing body with binocular vision and a 1400cc brain is an adequate biological form. It cannot cope with the quantity, complexity and quality of information it has accumulated; it is intimidated by the precision, speed and power of technology and it is biologically ill-equipped to cope with its new extraterrestrial environment.

The body is neither a very efficient nor very durable structure. It malfunctions often and fatigues quickly; its performance is determined by its age. It is susceptible to disease and is doomed to a certain and early death. Its survival parameters are very slim - it can survive only weeks without food, days without water and minutes without oxygen.

The body's LACK OF MODULAR DESIGN and its overactive immunological system make it difficult to replace malfunctioning organs. It might be the height of technological folly to consider the body obsolete in form and function, yet it might be the height of human realisations. For it is only when the body becomes aware of its present position that it can map its post-evolutionary strategies.

It is no longer a matter of perpetuating the human species by REPRODUCTION, but of enhancing male-female intercourse by human-machine interface. THE BODY IS OBSOLETE. We are at the end of philosophy and human physiology. Human thought recedes into the human past.

redesigning the body

redesigning the bodyIt is no longer meaningful to see the body as a site for the psyche or the social, but rather as a structure to be monitored and modified - the body not as a subject but as an object - NOT AN OBJECT OF DESIRE BUT AS AN OBJECT FOR DESIGNING.

The psycho-social period was characterised by the body circling itself, orbiting itself, illuminating and inspecting itself by physical prodding and metaphysical contemplation.

But having confronted its image of obsolescence, the body is traumatised to split from the realm of subjectivity and consider the necessity of re-examining and possibly redesigning its very structure. ALTERING THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE BODY RESULTS IN ADJUSTING AND EXTENDING ITS AWARENESS OF THE WORLD.

As an object, the body can be amplified and accelerated, attaining planetary escape velocity. It becomes a post-evolutionary projectile, departing and diversifying in form and function.

the hum of the hybrid

Technology transforms the nature of human existence, equalising the physical potential of bodies and standardising human sexuality. With fertilisation now occuring outside the womb and the possibility of nurturing the foetus in an artificial support system, THERE WILL TECHNICALLY BE NO BIRTH. And if the body can be redesigned in a modular fashion to facilitate the replacement of malfunctioning parts, then TECHNICALLY THERE WOULD BE NO REASON FOR DEATH - given the accessibility of replacements.

Death does not authenticate existence. It is an out-moded evolutionary strategy. The body need no longer be repaired, but could simply have parts replaced. Extending life no longer means "existing" but rather "being operational". Bodies need not age or deteriorate; they would not run down nor even fatigue; they would stall then start - possessing both the potential for renewal and reactivation.

In the extended space-time of extraterrestrial environments, THE BODY MUST BECOME IMMORTAL TO ADAPT. Utopian dreams become post-evolutionary imperatives. THIS IS NO MERE FAUSTIAN OPTION NOR SHOULD THERE BE ANY FRANKENSTEINIAN FEAR IN TAMPERING WITH THE BODY.

the anaesthesised body

The importance of technology is not simply in the pure power it generates but in the realm of abstraction it produces through its operational speed and its development of extended sense systems.

Technology pacifies the body and the world, and disconnects the body from many of its functions. DISTRAUGHT AND DISCONNECTED, THE BODY CAN ONLY RESORT TO INTERFACE AND SYMBIOSIS.

The body may not yet surrender its autonomy but certainly its mobility. The body plugged into a machine network needs to be pacified. In fact, to function in the future and to truly achieve a hybrid symbiosis the body will need to be increasingly anaesthetised.

the shedding of the skin

Off the Earth, the body's complexity, softness and wetness would be difficult to sustain. The strategy should be to HOLLOW, HARDEN and DEHYDRATE the body to make it more durable and less vulnerable.

The present organ-isation of the body is unnecessary. The solution to modifying the body is not to be found in its internal structure, but lies simply on its surface. THE SOLUTION IS NO MORE THAN SKIN DEEP.

The significant event in our evolutionary history was a change in the mode of locomotion. Future developments will occur with a change of skin. If we could engineer a SYNTHETIC SKIN which could absorb oxygen directly through its pores and could efficiently convert light into chemical nutrients, we could radically redesign the body, eliminating many of its redundant systems and malfunctioning organs - minimising toxin build-up in its chemistry.

THE HOLLOW BODY WOULD BE A BETTER HOST FOR TECHNOLOGICAL COMPONENTS.

high fidelity illusion

With teleoperation systems, it is possible to project human presence and perform physical actions in remote and extraterrestrial locations. A single operator could direct a colony of robots in different locations simultaneously, or scattered human experts might collectively control a particular surrogate robot.

Teleoperation systems would have to be more than hand-eye mechanisms. They would have to create kinesthetic feel, providing the sense of orientation, motion and body tension. Robots would have to be semi-autonomous, capable of "intelligent disobedience". With Teleautomation (Conway/Voz/Walker), forward simulation - with time and precision clutches - assists in overcoming the problem of real time-delays, allowing prediction to improve performance.

The experience of Telepresence (Minsky) becomes the high-fidelity illusion of Tele-existence (Tachi). ELECTRONIC SPACE BECOMES A MEDIUM OF ACTION RATHER THAN INFORMATION. It meshes the body with its machines in ever-increasing complexity and interactiveness. The body's form is enhanced and its functions are extended. ITS PERFORMANCE PARAMETERS ARE NEITHER LIMITED BY ITS PHYSIOLOGY NOR BY THE LOCAL SPACE IT OCCUPIES.

Electronic space restructures the body's architecture and multiplies its operational possibilities. The body performs by coupling the kinesthetic action of muscles and machine with the kinematic pure motion of the images it generates.

phantom body

Technologies are becoming better life-support systems for our images than for our bodies. IMAGES ARE IMMORTAL, BODIES ARE EPHEMERAL.

The body finds it increasingly difficult to match the expectations of its images. In the realm of multiplying and morphing images, the physical body's impotence is apparent. THE BODY NOW PERFORMS BEST AS ITS IMAGE.

Virtual Reality technology allows a transgression of boundaries between male/female, human/machine, time/space. The self becomes situated beyond the skin.

This is not a disconnecting or a splitting, but an EXTRUDING OF AWARENESS. What it means to be human is no longer the state of being immersed in genetic memory but rather in being reconfigured in the electromagnetic field of the circuit - IN THE REALM OF THE IMAGE.

fractal flesh

The self-similarity found throughout nature - the small-scale infinitely reflecting the large-scale - could be absorbed into the human/machine symbiosis, in terms of both form and function. Granted the evolutionary importance of the human hand, for example, a post-evolutionary strategy might see each of the fingers having its own hand, vastly amplifying and fine-tuning human dexterity.

Alternatively, PYRAMID-PERSONAGES, able to operate simultaneously through macro to micro scales, could experience space/time realms and relations perceptually veiled from our present physiological perspective. THE RECURSIVE BEING WOULD MORE EFFECTIVELY EXTRUDE ITS EXISTENCE THROUGH A TELEMATIC SCALING OF THE SENSES.

Consider

- a body that is directly wired into the Net - a body that stirs and is startled by the whispers and twitches of REMOTE AGENTS - other physical bodies in other places. AGENTS NOT AS VIRAL CODES BUT AS DISPLACED PRESENCES

- a body whose authenticity is grounded not in its individuality, but rather in the MULTIPLICITY of of remote agents that it hosts

- a body whose PHYSICALITY IS SPLIT - voltage-in to induce involuntary movements (from its net-connected computer muscle stimulation system) and voltage-out to actuate peripheral devices and to respond to remote transmissions

- a body whose pathology is not having a split personality, but whose advantage is having a split physiology (from psycho-social to cyber-systemic) . . a body that can collaborate and perform tasks REMOTELY INITIATED AND LOCALLY COMPLETED - at the same time, in the one physiology . . or a body whose left side is remotely guided and whose right side intuitively improvises

- a body that must perform in a technological realm where intention and action collapse, with no time to ponder - A BODY ACTING WITHOUT EXPECTATION, producing MOVEMENTS WITHOUT MEMORY. Can a body act with neither recall nor desire ? Can a body act without emotion ?

- a body of FRACTAL FLESH, whose agency can be electronically extruded on the Net - from one body to another body elsewhere. Not as a kind of remote-control cyber-Voodoo, but as the DISPLACING OF MOTIONS from one Net-connected physical body to another. Such a body's awareness would be neither "all-here" nor "all-there". Awareness and action would slide and shift between bodies. Agency could be shared in the one body or in a multiplicity of bodies in an ELECTRONIC SPACE OF DISTRIBUTED INTELLIGENCE

- a body with TELEMATIC SCALING OF THE SENSES, perceiving and operating beyond its biology and the local space and human scale it now occupies. Its VIRTUAL VISION augmenting and intensifying it retinal flicker

- a body remapped and reconfigured - not in genetic memory but rather in electronic circuitry. A body needing to function not with the affirmation of its historical and cultural recall but in a ZONE OF ERASURE - a body no longer merely an individual but a body that needs to act beyond its human metabolism and circadian rhythms

- a body directly wired into the Net, that moves not because of its internal stimulation, not because of its being remotely guided by another body (or a cluster of remote agents), BUT A BODY THAT QUIVERS AND OSCILLATES TO THE EBB AND FLOW OF NET ACTIVITY. A body that manifests the statistical and collective data flow, as a socio-neural compression algorithm. A body whose proprioception responds not to its internal nervous system but to the external stimulation of globally connected computer networks

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

9:27 AM

0

replies

tags -

artists,

body,

Cyborg,

media art,

performance

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> symbioticA

from: http://www.symbiotica.uwa.edu.au/research

from: http://www.symbiotica.uwa.edu.au/research

"SymbioticA is a research facility dedicated to artistic inquiry into new knowledge and technology with a strong interest in the life sciences. SymbioticA has resident researchers and students undertaking projects that explore and develop the links between the arts and a range of research areas such as neuroscience, plant biology, anatomy and human biology, tissue engineering, physics, bio-engineering, museology, anthropology, molecular biology, microscopy, animal welfare and ethics.

Having access to scientific laboratories and tools, SymbioticA is in a unique position to offer these resources for artistic research. Therefore, SymbioticA encourages and favours research projects that involve hands on development of technical skills and the use of scientific tools.

The research in SymbioticA is speculative in nature. SymbioticA strives to support non utilitarian, curiosity based, and philosophically motivated research.

In broad term the research ranges from identifying and developing new materials and subjects for artistic manipulation, researching strategies and implications of presenting living art in different contexts, and developing technologies and protocols as artistic tool kits. Some of the projects in SymbioticA are also very relevant to scientific research and the complexity of art and science collaborations is intensively explored.

Areas of continued research

Areas of continued research

• Art and Biology

In broad terms the main focus of research in SymbioticA is to do with the interaction between the life science, biotechnology, society and the arts. As an area of growing interest, SymbioticA is well positioned as one of the major international centres researching and developing art and biology projects. Beside the support for hands on art and biology projects, SymbioticA has already hosted philosophers, anthropologists and social scientists for short and long term research projects into art and biology.

• Art and Agriculture/ Art and Ecology

As a subset of art and biology and through the strong connections with the Faculty of Agriculture and natural Sciences, SymbioticA is interested in research in the somewhat contradictory areas of agriculture and ecology.

• Bioethics

As part of the engagement with debate over the implications of developments in the life sciences with culture and society; SymbioticA encourage research into the ethics of manipulating living systems for utilitarian, speculative and seemingly frivolous ends. Art can act as an important catalyst for ethical exploration. In addition some of the research in SymbioticA attempts to approach bioethics form a secular non-anthropocentric perspective.

• Neuroscience

SymbioticA has a long involvement with neuroscience as it is one of the main research areas of SymbioticA’s scientific director Prof. Stuart Bunt. Projects that deal with neuroscience and robotics are of particular interest. See www.fishandchips.uwa.edu.au

• Tissue Engineering

SymbioticA have built a reputation as the leading laboratory that investigates the in vitro growth and manipulation of living tissue in three dimensions. The work of The Tissue Culture & Art Project, and many other subsequent projects, guided the developments of protocols and specific techniques of tissue engineering.

• Bioreactor

The development of a life sustaining device for tissue engineered art is an area of investigation that requires expertise in diverse knowledge pools from biology, through engineering and fluid dynamics to art and display strategies. Artists in SymbioticA and scientists from the School of Anatomy and Human Biology have been researching the development of an “artistic” bioreactor for the last five years.

History_________________________________________________________________

SymbioticA was established in 2000 by cell biologist Professor Miranda Grounds, neuroscientist Professor Stuart Bunt and artist Oron Catts. Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr from the Tissue Culture and Art Project (TC&A) had been working as artists/researchers in residence in the School of Anatomy and Human Biology and the Lions Eye Institute since 1996. The shared vision of Grounds, Bunt and Catts for a permanent space for artists to engage with science in various capacities led to the building of the artists’ studio/lab on the second floor of the School of Anatomy and Human Biology at The University of Western Australia.

Funding for the space was provided by the Lotteries Foundation of WA and The University of Western Australia

School of Anatomy and Human Biology and History with Artists______

The School of Anatomy and Human Biology has a long tradition of working with artists, with the departmental corridors lined with art and scientific images. Hans Arkeveld, sculptor and painter, has been working with the department for the last three decades. Other artists have come and gone on an ad hoc basis, but although many observed and gained inspiration there, it was not until Catts and Zurr entered the laboratories and used the tools of scientific research to produce their art work that the potential of a space such as SymbioticA was conceived.

Winners of the 2007 inaugural Golden Nica for Hybrid Arts in the Prix Ars Electronica

SymbioticA is an artistic laboratory dedicated to the research, learning and critique of life sciences. SymbioticA is the first research laboratory of its kind, in that it enables artists to engage in wet biology practices in a biological science department.

SymbioticA sets out to provide a situation where interdisciplinary research and other knowledge and concept generating activities can take place. It provides an opportunity for researchers to pursue curiosity-based explorations free of the demands and constraints associated with the current culture of scientific research while still complying with regulations. SymbioticA also offers a new means of artistic inquiry, one in which artists actively use the tools and technologies of science, not just to comment about them, but also to explore their possibilities.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

9:20 AM

0

replies

tags -

art + science,

artists,

genetic art,

Labs

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> Eduardo Kac, "GFP Bunny", 2000

http://www.ekac.org/gfpbunny.html

http://www.ekac.org/gfpbunny.html

"My transgenic artwork "GFP Bunny" comprises the creation of a green fluorescent rabbit, the public dialogue generated by the project, and the social integration of the rabbit. GFP stands for green fluorescent protein. "GFP Bunny" was realized in 2000 and first presented publicly in Avignon, France. Transgenic art, I proposed elsewhere [1], is a new art form based on the use of genetic engineering to transfer natural or synthetic genes to an organism, to create unique living beings. This must be done with great care, with acknowledgment of the complex issues thus raised and, above all, with a commitment to respect, nurture, and love the life thus created.

WELCOME, ALBA

I will never forget the moment when I first held her in my arms, in Jouy-en-Josas, France, on April 29, 2000. My apprehensive anticipation was replaced by joy and excitement. Alba -- the name given her by my wife, my daughter, and I -- was lovable and affectionate and an absolute delight to play with. As I cradled her, she playfully tucked her head between my body and my left arm, finding at last a comfortable position to rest and enjoy my gentle strokes. She immediately awoke in me a strong and urgent sense of responsibility for her well-being.

Alba is undoubtedly a very special animal, but I want to be clear that her formal and genetic uniqueness are but one component of the "GFP Bunny" artwork. The "GFP Bunny" project is a complex social event that starts with the creation of a chimerical animal that does not exist in nature (i.e., "chimerical" in the sense of a cultural tradition of imaginary animals, not in the scientific connotation of an organism in which there is a mixture of cells in the body) and that also includes at its core: 1) ongoing dialogue between professionals of several disciplines (art, science, philosophy, law, communications, literature, social sciences) and the public on cultural and ethical implications of genetic engineering; 2) contestation of the alleged supremacy of DNA in life creation in favor of a more complex understanding of the intertwined relationship between genetics, organism, and environment; 3) extension of the concepts of biodiversity and evolution to incorporate precise work at the genomic level; 4) interspecies communication between humans and a transgenic mammal; 5) integration and presentation of "GFP Bunny" in a social and interactive context; 6) examination of the notions of normalcy, heterogeneity, purity, hybridity, and otherness; 7) consideration of a non-semiotic notion of communication as the sharing of genetic material across traditional species barriers; 8) public respect and appreciation for the emotional and cognitive life of transgenic animals; 9) expansion of the present practical and conceptual boundaries of artmaking to incorporate life invention.

GLOW IN THE FAMILY

"Alba", the green fluorescent bunny, is an albino rabbit. This means that, since she has no skin pigment, under ordinary environmental conditions she is completely white with pink eyes. Alba is not green all the time. She only glows when illuminated with the correct light. When (and only when) illuminated with blue light (maximum excitation at 488 nm), she glows with a bright green light (maximum emission at 509 nm). She was created with EGFP, an enhanced version (i.e., a synthetic mutation) of the original wild-type green fluorescent gene found in the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria. EGFP gives about two orders of magnitude greater fluorescence in mammalian cells (including human cells) than the original jellyfish gene [2].

The first phase of the "GFP Bunny" project was completed in February 2000 with the birth of "Alba" in Jouy-en-Josas, France. This was accomplished with the invaluable assistance of zoosystemician Louis Bec [3] and scientists Louis-Marie Houdebine and Patrick Prunet [4]. Alba's name was chosen by consensus between my wife Ruth, my daughter Miriam, and myself. The second phase is the ongoing debate, which started with the first public announcement of Alba's birth, in the context of the Planet Work conference, in San Francisco, on May 14, 2000. The third phase will take place when the bunny comes home to Chicago, becoming part of my family and living with us from this point on.

FROM DOMESTICATION TO SELECTIVE BREEDING

The human-rabbit association can be traced back to the biblical era, as exemplified by passages in the books Leviticus (Lev. 11:5) and Deuteronomy (De. 14:7), which make reference to saphan, the Hebrew word for rabbit. Phoenicians seafarers discovered rabbits on the Iberian Peninsula around 1100 BC and, thinking that these were Hyraxes (also called Rock Dassies), called the land "i-shepan-im" (land of the Hyraxes). Since the Iberian Peninsula is north of Africa, relative geographic position suggests that another Punic derivation comes from sphan, "north". As the Romans adapted "i-shepan-im" to Latin, the word Hispania was created -- one of the etymological origins of Spain. In his book III the Roman geographer Strabo (ca. 64 BC - AD 21) called Spain "the land of rabbits". Later on, the Roman emperor Servius Sulpicius Galba (5 BC - AD 69), whose reign was short-lived (68-69 AD), issued a coin on which Spain is represented with a rabbit at her feet. Although semi-domestication started in the Roman period, in this initial phase rabbits were kept in large walled pens and were allowed to breed freely.

Humans started to play a direct role in the evolution of the rabbit from the sixth to the tenth centuries AD, when monks in southern France domesticated and bred rabbits under more restricted conditions [5]. Originally from the region comprised by southwestern Europe and North Africa, the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is the ancestor of all domestic breeds. Since the sixth century, because of its sociable nature the rabbit increasingly has become integrated into human families as a domestic companion. Such human-induced selective breeding created the morphological diversity found in rabbits today. The first records describing a variety of fur colors and sizes distinct from wild breeds date from the sixteenth century. It was not until the eighteenth century that selective breeding resulted in the Angora rabbit, which has a uniquely thick and beautiful wool coat. The process of domestication carried out since the sixth century, coupled with ever increasing worldwide migration and trade, resulted in many new breeds and in the introduction of rabbits into new environments different from their place of origin. While there are well over 100 known breeds of rabbit around the world, "recognized" pedigree breeds vary from one country to another. For example, the American Rabbit Breeders Association (ARBA) "recognizes" 45 breeds in the U.S.A., with more under development.

In addition to selective breeding, naturally occurring genetic variations also contributed to morphological diversity. The albino rabbit, for example, is a natural (recessive) mutation which in the wild has minimal chances of survival (due to lack of proper pigmentation for camouflage and keener vision to spot prey). However, because it has been bred by humans, it can be found widely today in healthy populations. The human preservation of albino animals is also connected to ancient cultural traditions: almost every Native American tribe believed that albino animals had particular spiritual significance and had strict rules to protect them [6].FROM BREEDING TO TRANSGENIC ART

"GFP Bunny" is a transgenic artwork and not a breeding project. The differences between the two include the principles that guide the work, the procedures employed, and the main objectives. Traditionally, animal breeding has been a multi-generational selection process that has sought to create pure breeds with standard form and structure, often to serve a specific performative function. As it moved from rural milieus to urban environments, breeding de-emphasized selection for behavioral attributes but continued to be driven by a notion of aesthetics anchored on visual traits and on morphological principles. Transgenic art, by contrast, offers a concept of aesthetics that emphasizes the social rather than the formal aspects of life and biodiversity, that challenges notions of genetic purity, that incorporates precise work at the genomic level, and that reveals the fluidity of the concept of species in an ever increasingly transgenic social context.

As a transgenic artist, I am not interested in the creation of genetic objects, but on the invention of transgenic social subjects. In other words, what is important is the completely integrated process of creating the bunny, bringing her to society at large, and providing her with a loving, caring, and nurturing environment in which she can grow safe and healthy. This integrated process is important because it places genetic engineering in a social context in which the relationship between the private and the public spheres are negotiated. In other words, biotechnology, the private realm of family life, and the social domain of public opinion are discussed in relation to one another. Transgenic art is not about the crafting of genetic objets d'art, either inert or imbued with vitality. Such an approach would suggest a conflation of the operational sphere of life sciences with a traditional aesthetics that privileges formal concerns, material stability, and hermeneutical isolation. Integrating the lessons of dialogical philosophy [7] and cognitive ethology [8], transgenic art must promote awareness of and respect for the spiritual (mental) life of the transgenic animal. The word "aesthetics" in the context of transgenic art must be understood to mean that creation, socialization, and domestic integration are a single process. The question is not to make the bunny meet specific requirements or whims, but to enjoy her company as an individual (all bunnies are different), appreciated for her own intrinsic virtues, in dialogical interaction.One very important aspect of "GFP Bunny" is that Alba, like any other rabbit, is sociable and in need of interaction through communication signals, voice, and physical contact. As I see it, there is no reason to believe that the interactive art of the future will look and feel like anything we knew in the twentieth century. "GFP Bunny" shows an alternative path and makes clear that a profound concept of interaction is anchored on the notion of personal responsibility (as both care and possibility of response). "GFP Bunny" gives continuation to my focus on the creation, in art, of what Martin Buber called dialogical relationship [9], what Mikhail Bakhtin called dialogic sphere of existence [10], what Emile Benveniste called intersubjectivity [11], and what Humberto Maturana calls consensual domains [12]: shared spheres of perception, cognition, and agency in which two or more sentient beings (human or otherwise) can negotiate their experience dialogically. The work is also informed by Emmanuel Levinas' philosophy of alterity [13], which states that our proximity to the other demands a response, and that the interpersonal contact with others is the unique relation of ethical responsibility. I create my works to accept and incorporate the reactions and decisions made by the participants, be they eukaryotes or prokaryotes [14]. This is what I call the human-plant-bird-mammal-robot-insect-bacteria interface.

In order to be practicable, this aesthetic platform--which reconciles forms of social intervention with semantic openness and systemic complexity--must acknowledge that every situation, in art as in life, has its own specific parameters and limitations. So the question is not how to eliminate circumscription altogether (an impossibility), but how to keep it indeterminate enough so that what human and nonhuman participants think, perceive, and do when they experience the work matters in a significant way. My answer is to make a concerted effort to remain truly open to the participant's choices and behaviors, to give up a substantial portion of control over the experience of the work, to accept the experience as-it-happens as a transformative field of possibilities, to learn from it, to grow with it, to be transformed along the way. Alba is a participant in the "GFP Bunny" transgenic artwork; so is anyone who comes in contact with her, and anyone who gives any consideration to the project. A complex set of relationships between family life, social difference, scientific procedure, interspecies communication, public discussion, ethics, media interpretation, and art context is at work.

Throughout the twentieth century art progressively moved away from pictorial representation, object crafting, and visual contemplation. Artists searching for new directions that could more directly respond to social transformations gave emphasis to process, concept, action, interaction, new media, environments, and critical discourse. Transgenic art acknowledges these changes and at the same time offers a radical departure from them, placing the question of actual creation of life at the center of the debate. Undoubtedly, transgenic art also develops in a larger context of profound shifts in other fields. Throughout the twentieth century physics acknowledged uncertainty and relativity, anthropology shattered ethnocentricity, philosophy denounced truth, literary criticism broke away from hermeneutics, astronomy discovered new planets, biology found "extremophile" microbes living in conditions previously believed not capable of supporting life, molecular biology made cloning a reality.

Transgenic art acknowledges the human role in rabbit evolution as a natural element, as a chapter in the natural history of both humans and rabbits, for domestication is always a bidirectional experience. As humans domesticate rabbits, so do rabbits domesticate their humans. If teleonomy is the apparent purpose in the organization of living systems [15], then transgenic art suggests a non-utilitarian and more subtle approach to the debate. Moving beyond the metaphor of the artwork as a living organism into a complex embodiment of the trope, transgenic art opens a nonteleonomic domain for the life sciences. In other words, in the context of transgenic art humans exert influence in the organization of living systems, but this influence does not have a pragmatic purpose. Transgenic art does not attempt to moderate, undermine, or arbitrate the public discussion. It seeks to offer a new perspective that offers ambiguity and subtlety where we usually only find affirmative ("in favor") and negative ("against") polarity. "GFP Bunny" highlights the fact that transgenic animals are regular creatures that are as much part of social life as any other life form, and thus are deserving of as much love and care as any other animal [16].

In developing the "GFP Bunny" project I have paid close attention and given careful consideration to any potential harm that might be caused. I decided to proceed with the project because it became clear that it was safe [17]. There were no surprises throughout the process: the genetic sequence responsible for the production of the green fluorescent protein was integrated into the genome through zygote microinjection [18]. The pregnancy was carried to term successfully. "GFP Bunny" does not propose any new form of genetic experimentation, which is the same as saying: the technologies of microinjection and green fluorescent protein are established well-known tools in the field of molecular biology. Green fluorescent protein has already been successfully expressed in many host organisms, including mammals [19]. There are no mutagenic effects resulting from transgene integration into the host genome. Put another way: green fluorescent protein is harmless to the rabbit. It is also important to point out that the "GFP Bunny" project breaks no social rule: humans have determined the evolution of rabbits for at least 1400 years.ALTERNATIVES TO ALTERITY

As we negotiate our relationship with our lagomorph companion [20], it is necessary to think rabbit agency without anthropomorphizing it. Relationships are not tangible, but they form a fertile field of investigation in art, pushing interactivity into a literal domain of intersubjectivity. Everything exists in relationship to everything else. Nothing exists in isolation. By focusing my work on the interconnection between biological, technological, and hybrid entities I draw attention to this simple but fundamental fact. To speak of interconnection or intersubjectivity is to acknowledge the social dimension of consciousness. Therefore, the concept of intersubjectivity must take into account the complexity of animal minds. In this context, and particularly in regard to "GFP Bunny", one must be open to understanding the rabbit mind, and more specifically to Alba's unique spirit as an individual. It is a common misconception that a rabbit is less intelligent than, for example, a dog, because, among other peculiarities, it seems difficult for a bunny to find food right in front of her face. The cause of this ordinary phenomenon becomes clear when we consider that the rabbit's visual system has eyes placed high and to the sides of the skull, allowing the rabbit to see nearly 360 degrees. As a result, the rabbit has a small blind spot of about l0 degrees directly in front of her nose and below her chin [21]. Although rabbits do not see images as sharply as we do, they are able to recognize individual humans through a combination of voice, body movements, and scent as cues, provided that humans interact with their rabbits regularly and don't change their overall configuration in dramatic ways (such as wearing a costume that alters the human form or using a strong perfume). Understanding how the rabbit sees the world is certainly not enough to appreciate its consciousness but it allows us to gain insights about its behavior, which leads us to adapt our own to make life more comfortable and pleasant for everyone.

Alba is a healthy and gentle mammal. Contrary to popular notions of the alleged monstrosity of genetically engineered organisms, her body shape and coloration are exactly of the same kind we ordinarily find in albino rabbits. Unaware that Alba is a glowing bunny, it is impossible for anyone to notice anything unusual about her. Therefore Alba undermines any ascription of alterity predicated on morphology and behavioral traits. It is precisely this productive ambiguity that sets her apart: being at once same and different. As is the case in most cultures, our relationship with animals is profoundly revealing of ourselves. Our daily coexistence and interaction with members of other species remind us of our uniqueness as humans. At the same time, it allow us to tap into dimensions of the human spirit that are often suppressed in daily life--such as communication without language--that reveal how close we really are to nonhumans. The more animals become part of our domestic life, the further we move breeding away from functionality and animal labor. Our relationship with other animals shifts as historical conditions are transformed by political pressures, scientific discoveries, technological development, economic opportunities, artistic invention, and philosophical insights. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, as we transform our understanding of human physical boundaries by introducing new genes into developed human organisms, our communion with animals in our environment also changes. Molecular biology has demonstrated that the human genome is not particularly important, special, or different. The human genome is made of the same basic elements as other known life forms and can be seen as part of a larger genomic spectrum rich in variation and diversity.

Western philosophers, from Aristotle [22] to Descartes [23], from Locke [24] to Leibniz [25], from Kant [26] to Nietsche [27] and Buber [28], have approached the enigma of animality in a multitude of ways, evolving in time and elucidating along the way their views of humanity. While Descartes and Kant possessed a more condescending view of the spiritual life of animals (which can also be said of Aristotle), Locke, Leibniz, Nietsche, and Buber are -- in different degrees -- more tolerant towards our eukaryotic others [29]. Today, our ability to generate life through the direct method of genetic engineering prompts a re-evaluation of the cultural objectification and the personal subjectification of animals, and in so doing it renews our investigation of the limits and potentialities of what we call humanity. I do not believe that genetic engineering eliminates the mystery of what life is; to the contrary, it reawakens in us a sense of wonder towards the living. We will only think that biotechnology eliminates the mystery of life if we privilege it in detriment to other views of life (as opposed to seeing biotechnology as one among other contributions to the larger debate) and if we accept the reductionist view (not shared by many biologists) that life is purely and simply a matter of genetics. Transgenic art is a firm rejection of this view and a reminder that communication and interaction between sentient and nonsentient actants lies at the core of what we call life. Rather than accepting the move from the complexity of life processes to genetics, transgenic art gives emphasis to the social existence of organisms, and thus highlights the evolutionary continuum of physiological and behavioral characteristics between the species. The mystery and beauty of life is as great as ever when we realize our close biological kinship with other species and when we understand that from a limited set of genetic bases life has evolved on Earth with organisms as diverse as bacteria, plants, insects, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

TRANSGENESIS, ART, AND SOCIETY

The success of human genetic therapy suggests the benefits of altering the human genome to heal or to improve the living conditions of fellow humans [30]. In this sense, the introduction of foreign genetic material in the human genome can be seen not only as welcome but as desirable. Developments in molecular biology, such as the above example, are at times used to raise the specter of eugenics and biological warfare, and with it the fear of banalization and abuse of genetic engineering. This fear is legitimate, historically grounded, and must be addressed. Contributing to the problem, companies often employ empty rhetorical strategies to persuade the public, thus failing to engage in a serious debate that acknowledges both the problems and benefits of the technology. [31] There are indeed serious threats, such as the possible loss of privacy regarding one's own genetic information, and unacceptable practices already underway, such as biopiracy (the appropriation and patenting of genetic material from its owners without explicit permission).

As we consider these problems, we can not ignore the fact that a complete ban on all forms of genetic research would prevent the development of much needed cures for the many devastating diseases that now ravage human and nonhumankind. The problem is even more complex. Should such therapies be developed successfully, what sectors of society will have access to them? Clearly, the question of genetics is not purely and simply a scientific matter, but one that is directly connected to political and economic directives. Precisely for this reason, the fear raised by both real and potential abuse of this technology must be channeled productively by society. Rather than embracing a blind rejection of the technology, which is undoubtedly already a part of the new bioscape, citizens of open societies must make an effort to study the multiple views on the subject, learn about the historical background surrounding the issues, understand the vocabulary and the main research efforts underway, develop alternative views based on their own ideas, debate the issue, and arrive at their own conclusions in an effort to generate mutual understanding. Inasmuch as this seems a daunting task, drastic consequences may result from hype, sheer opposition, or indifference.

This is where art can also be of great social value. Since the domain of art is symbolic even when intervening directly in a given context [32], art can contribute to reveal the cultural implications of the revolution underway and offer different ways of thinking about and with biotechnology. Transgenic art is a mode of genetic inscription that is at once inside and outside of the operational realm of molecular biology, negotiating the terrain between science and culture. Transgenic art can help science to recognize the role of relational and communicational issues in the development of organisms. It can help culture by unmasking the popular belief that DNA is the "master molecule" through an emphasis on the whole organism and the environment (the context). At last, transgenic art can contribute to the field of aesthetics by opening up the new symbolic and pragmatic dimension of art as the literal creation of and responsibility for life.

Gepostet von

Nina Wenhart ...

hh:mm

9:10 AM

0

replies

tags -

artists,

genetic art,

media art

![]()

Bookmark this post:blogger tutorials

Social Bookmarking Blogger Widget |

>> additional class blogs

>> labels

- Alan Turing (2)

- animation (1)

- AR (1)

- archive (14)

- Ars Electronica (4)

- art (3)

- art + technology (6)

- art + science (1)

- artificial intelligence (2)

- artificial life (3)

- artistic molecules (1)

- artistic software (21)

- artists (68)

- ASCII-Art (1)

- atom (2)

- atomium (1)

- audiofiles (4)

- augmented reality (1)

- Baby (1)

- basics (1)

- body (1)

- catalogue (3)

- CAVE (1)

- code art (23)

- cold war (2)

- collaboration (7)

- collection (1)

- computer (12)

- computer animation (15)

- computer graphics (22)

- computer history (21)

- computer programming language (11)

- computer sculpture (2)

- concept art (3)

- conceptual art (2)

- concrete poetry (1)

- conference (3)

- conferences (2)

- copy-it-right (1)

- Critical Theory (5)

- culture industry (1)

- culture jamming (1)

- curating (2)

- cut up (3)

- cybernetic art (9)

- cybernetics (10)

- cyberpunk (1)

- cyberspace (1)

- Cyborg (4)

- data mining (1)

- data visualization (1)

- definitions (7)

- dictionary (2)

- dream machine (1)

- E.A.T. (2)

- early exhibitions (22)

- early new media (42)

- engineers (3)

- exhibitions (14)

- expanded cinema (1)

- experimental music (2)

- female artists and digital media (1)

- festivals (3)

- film (3)

- fluxus (1)

- for alyor (1)

- full text (1)

- game (1)

- generative art (4)

- genetic art (3)

- glitch (1)

- glossary (1)

- GPS (1)

- graffiti (2)

- GUI (1)

- hackers and painters (1)

- hacking (7)

- hacktivism (5)

- HCI (2)

- history (23)

- hypermedia (1)

- hypertext (2)

- information theory (3)

- instructions (2)

- interactive art (9)

- internet (10)

- interview (3)

- kinetic sculpture (2)

- Labs (8)

- lecture (1)

- list (1)

- live visuals (1)

- magic (1)

- Manchester Mark 1 (1)

- manifesto (6)

- mapping (1)

- media (2)

- media archeology (1)

- media art (38)

- media theory (1)

- minimalism (3)

- mother of all demos (1)

- mouse (1)

- movie (1)

- musical scores (1)

- netart (10)

- open source (6)

- open source - against (1)

- open space (2)

- particle systems (2)

- Paul Graham (1)

- performance (4)

- phonesthesia (1)

- playlist (1)

- poetry (2)

- politics (1)

- processing (4)

- programming (9)

- projects (1)

- psychogeography (2)

- publications (36)

- quotes (2)

- radio art (1)

- re:place (1)

- real time (1)

- review (2)

- ridiculous (1)

- rotten + forgotten (8)

- sandin image processor (1)

- scientific visualization (2)

- screen-based (4)

- siggraph (1)

- situationists (4)

- slide projector (1)

- slit scan (1)

- software (5)

- software studies (2)

- Stewart Brand (1)

- surveillance (3)

- systems (1)

- tactical media (11)

- tagging (2)

- technique (1)

- technology (2)

- telecommunication (4)

- telematic art (4)

- text (58)

- theory (23)

- timeline (4)

- Turing Test (1)

- ubiquitious computing (1)

- unabomber (1)

- video (14)

- video art (5)

- video synthesizer (1)

- virtual reality (7)

- visual music (6)

- VR (1)

- Walter Benjamin (1)

- wearable computing (2)

- what is? (1)

- William's Tube (1)

- world fair (5)

- world machine (1)

- Xerox PARC (2)

>> cloudy with a chance of tags

followers

.........

- Nina Wenhart ...

- ... is a Media Art historian and researcher. She holds a PhD from the University of Art and Design Linz where she works as an associate professor. Her PhD-thesis is on "Speculative Archiving and Digital Art", focusing on facial recognition and algorithmic bias. Her Master Thesis "The Grammar of New Media" was on Descriptive Metadata for Media Arts. For many years, she has been working in the field of archiving/documenting Media Art, recently at the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Media.Art.Research and before as the head of the Ars Electronica Futurelab's videostudio, where she created their archives and primarily worked with the archival material. She was teaching the Prehystories of New Media Class at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) and in the Media Art Histories program at the Danube University Krems.